In Sulmona, Easter Drama in the Piazza

In northern Italy, the death and Resurrection of Christ is celebrated symbolically at Easter mass, followed by a huge family lunch and the cutting of the colomba, an Easter cake shaped like the dove of peace. In many parts of southern Italy, Easter is not only celebrated but also lived, starting at the latest on Holy Thursday, which is when I arrived in Sulmona, the ancient capital of the mountainous Abruzzi region.

”You’ve returned for the procession,” exclaimed one of my host’s delighted friends as I entered the crowded Piazza XX Settembre. To all appearances, Sulmona’s medieval Easter procession had already begun, so many people were gathered there under the brooding statue of Ovid, the Latin poet, born in Sulmona in 43 B.C. But no, the friend went on to explain: ”It’s always like this after 5 P.M. This is the daily passeggiata, not the processione. If you don’t see someone for two days here, you know something’s wrong.”

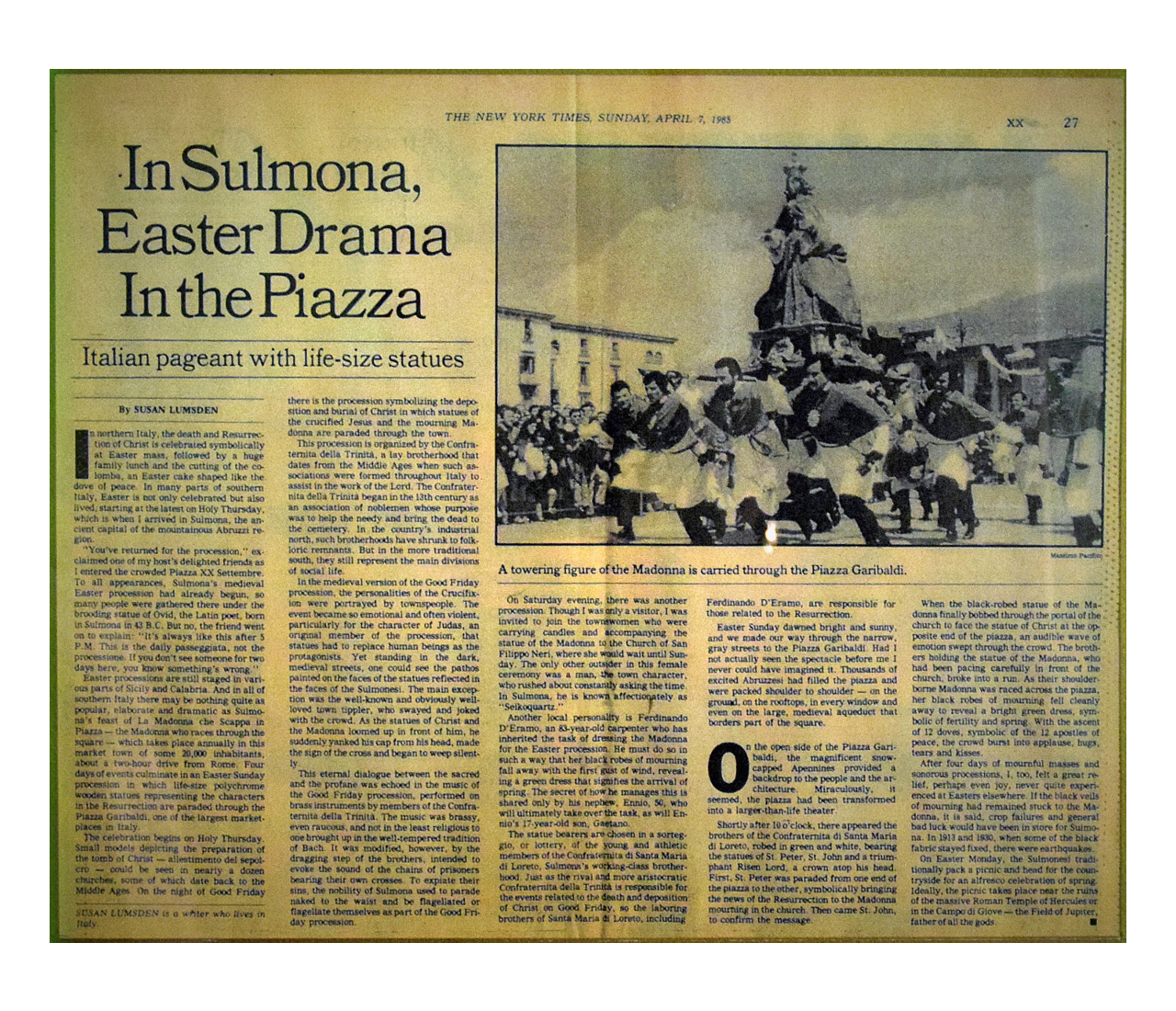

Easter processions are still staged in various parts of Sicily and Calabria. And in all of southern Italy there may be nothing quite as popular, elaborate and dramatic as Sulmona’s feast of La Madonna che Scappa in Piazza – the Madonna who races through the square – which takes place annually in this market town of some 20,000 inhabitants, about a two-hour drive from Rome. Four days of events culminate in an Easter Sunday procession in which life-size polychrome wooden statues representing the characters in the Resurrection are paraded through the Piazza Garibaldi, one of the largest marketplaces in Italy.

The celebration begins on Holy Thursday. Small models depicting the preparation of the tomb of Christ – allestimento del sepolcro – could be seen in nearly a dozen churches, some of which date back to the Middle Ages. On the night of Good Friday there is the procession symbolizing the deposition and burial of Christ in which statues of the crucified Jesus and the mourning Madonna are paraded through the town.

This procession is organized by the Confraternita della Trinit a, a lay brotherhood that dates from the Middle Ages when such associations were formed throughout Italy to assist in the work of the Lord. The Confraternita della Trinit a began in the 13th century as an association of noblemen whose purpose was to help the needy and bring the dead to the cemetery. In the country’s industrial north, such brotherhoods have shrunk to folkloric remnants. But in the more traditional south, they still represent the main divisions of social life.

In the medieval version of the Good Friday procession, the personalities of the Crucifixion were portrayed by townspeople. The event became so emotional and often violent, particularly for the character of Judas, an original member of the procession, that statues had to replace human beings as the protagonists. Yet standing in the dark, medieval streets, one could see the pathos painted on the faces of the statues reflected in the faces of the Sulmonesi. The main exception was the well-known and obviously well- loved town tippler, who swayed and joked with the crowd. As the statues of Christ and the Madonna loomed up in front of him, he suddenly yanked his cap from his head, made the sign of the cross and began to weep silently.

This eternal dialogue between the sacred and the profane was echoed in the music of the Good Friday procession, performed on brass instruments by members of the Confraternita della Trinit a. The music was brassy, even raucous, and not in the least religious to one brought up in the well-tempered tradition of Bach. It was modified, however, by the dragging step of the brothers, intended to evoke the sound of the chains of prisoners bearing their own crosses. To expiate their sins, the nobility of Sulmona used to parade naked to the waist and be flagellated or flagellate themselves as part of the Good Friday procession.

On Saturday evening, there was another procession. Though I was only a visitor, I was invited to join the townswomen who were carrying candles and accompanying the statue of the Madonna to the Church of San Filippo Neri, where she would wait until Sunday. The only other outsider in this female ceremony was a man, the town character, who rushed about constantly asking the time. In Sulmona, he is known affectionately as ”Seikoquartz.”

Fonte: New York Times